I too found a filmic connection to

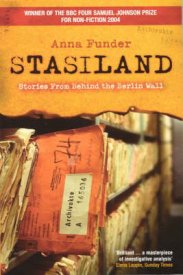

Stasiland, but this time it's the Oscar-winning film

The Lives of Others, which explored a tiny element of the work of the secret police (the Stasi) in the former East Germany. After seeing it I had an urge to find out more about the extraordinary deceptions and manipulations to which a population of 17 million was being subjected right up until 1989, not in North Korea or deepest Africa, but in Western Europe, right under our noses. Anna Funder’s award-winning

Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall, is just the ticket.

Spliced in with the human stories at its heart, Funder gives revealing (to an historical ignoramus like me) and even thrilling accounts of, in this order, the collapse of East Germany (or the GDR), the creation of the state, and the building of the Wall. It’s thrilling because the prose is novelistic, and while some may baulk at Funder’s rich fund of metaphors, her personalisation of her account (”I am hung over and steer myself like a car through the crowds at Alexanderplatz station…”) or the pervasive tone of

oh-the-humanity, I found it all made for a more richly human experience than a drier, more academic text might.

What Funder brings out brilliantly is the dark comedy inherent in what the GDR created for its people: the bizarre non-sexual Lipsi dance; the TV propaganda station with the giveaway name The Black Channel; swimming pools where swimming is permitted only between 4 and 6pm on Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays; and what Funder calls “an assortment of fundamental fictions” which the East German people were required to acknowledge as fact:

such as the idea that human nature is a work-in-progress which can be improved upon, and that Communism is the way to do it … that East Germans were not the Germans responsible (even in part) for the Holocaust; that the GDR was a multi-party democracy; that socialism was peace-loving; that there were no former Nazis left in the country; and that, under socialism, prostitution did not exist.

All these ignored the problem that, even if the GDR had been a socialist utopia, the fact that this way of life was not chosen by the people but forced upon them, negates any worth it might have had. The Party might have noted that if this “experiment on people” was really such a success, they might have wanted to stay. And then there is the Berlin Wall itself. For those of us who grew up with it and took it for granted, this might be the first opportunity to look on it from a distance and with the absurdity it deserves: a wall built around half of a city to stop the people outside getting in: but built

by the people outside (or their leaders ‘on their behalf’). And leaving the GDR was another rich source of almost comic contradiction:

By this time Charlie stood under formal suspicion of the crime of ‘Attempting to Flee the Republic.’ He and Miriam had put in applications to leave the GDR. Such applications were sometimes granted because the GDR, unlike any other eastern European country, could rid itself of malcontents by ditching them into West Germany, where they were automatically welcomed as citizens. The Stasi put all applications under extreme scrutiny. People who applied to leave were, unsurprisingly, suspected of wanting to leave which was, other than by this long-winded and arbitrary process, a crime. An ‘application to leave’ was legal, but the authorities might, if the fancy took them, choose to see it as a statement of why you didn’t like the GDR. In that case it became Hetzschrift (a smear) or a Schmahschrift (a libel) and therefore a criminal offence. On 26 August 1980 Charlie Weber was arrested and held in a remand cell.

It’s passages like this which make you understand why Funder chose

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as the source of one of her epigraphs for the book. And the humour which the situations tread so close to can only be smiled at for so long, before one recalls the lives stunted, wasted, reversed and ruined under the Stasi’s watch.

She proceeds sometimes in gripping narratives of individuals’ struggles against the regime (such as Miriam and Charlie, above), and elsewhere in apparently irrelevant accounts of her own time writing the book, but which invariably lead to highly pertinent observations. These include the appalling experiences of her landlady, Julia, one of those who, when the Wall fell and reunification followed, “did not gain a new life, but simply lost the old one.” She also meets former Stasi men and Party workers, who have lost all their power but (and perhaps as a result) none of their righteous belief in the System.

In the middle of the book, as though to buoy herself up for her work (”I’m making portraits of people, East Germans, of whom there will be none left in a generation. This is working against forgetting, and against time”) in the middle of such infectious madness, Funder reports another conversation with her landlady. Julia tells her: “For anyone to understand a regime like the GDR, the stories of ordinary people must be told. Not just the activists or the famous writers. You have to look at how normal people manage with such things in their pasts.” We nod appreciatively, and sympathise with Funder as she replies: “I think I’m losing track of normal.”