Shade

New Member

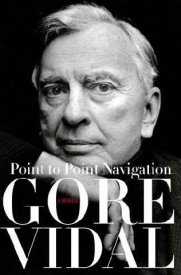

If ever your life feels a little thin or uneventful, blame Gore Vidal. He's had enough event and diversion in his life for five or six of us, and he keeps making us feel even worse by not only telling us about them in superbly written memoirs, but looking out of the cover at us all handsome and assured, both in youth and old age:

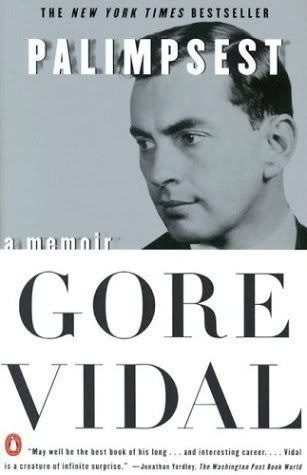

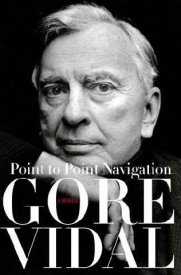

First there was Palimpsest (1995), dealing with his early life, which Martin Amis called "a tremendous read, down and dirty from start to finish. It is also a proud and serious and truthful book." Now Vidal gives us Point to Point Navigation, subtitled A Memoir 1964 - 2006.

And it is full of everything we have come to expect. Strange stories of all the great and good of the American twentieth century, from the very very famous to the known-in-certain-circles. Vidal's life has been not just more eventful than most, but lived at a more rarefied level; he was brought up among the renowned and the ruling classes, and so the line for him between the personal and the political has always been a thin one.

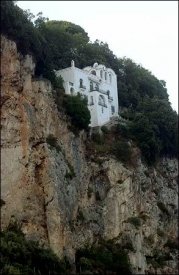

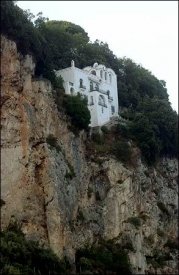

And there is a good reason for his interest in remembrance, and how he will be viewed in retrospect. Vidal is now 81 years old, and the spectre of death shadows most of the book. There will not, we suspect, be a third volume. He is writing in "the awful year 2005," after his first full year spent without his partner of 53 years, Howard Auster, and making the move for health reasons back to LA and away from his beloved La Rondinaia, the extraordinary home on the cliffs of Ravello on the Amalfi coast in Italy, where he and Auster had lived since 1963.

The memoir is less structured than Palimpsest, taking almost a diaristic form as he reflects both on the things that happen to him during 2005, the events in the world, and the people he knew whose deaths invoke a flurry of anecdotes. If the book had been more orderly, there is no doubt that Vidal would have left the strongest material to the end, instead of one-third in where it now appears. This is his report of the death of his partner Howard Auster in November 2003: the long struggle from illness to illness, the childlike reduction in his life, and most movingly, an extraordinary account of how Vidal looked into Auster's still-alert eyes after his heart stopped and held his gaze as he watched life ebb away from him. It is worth, as they say, the price of admission alone and if it doesn't move you to weeping then you should have your tear ducts checked by a qualified professional.

So strong is the feeling of mortality throughout the book (assisted by the black cover) that it almost feels like a posthumous publication. Vidal is still vital however, and the effortless quality of his prose reminds us that although he is "moving, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked exit," he is still fully with us.

And I do not want to suggest that the book is overwhelmingly gloomy or morbid. There is plenty of Vidal's wit in evidence, and his contempt for the current (and most past) American administration, and his country's cultural mores.

First there was Palimpsest (1995), dealing with his early life, which Martin Amis called "a tremendous read, down and dirty from start to finish. It is also a proud and serious and truthful book." Now Vidal gives us Point to Point Navigation, subtitled A Memoir 1964 - 2006.

And it is full of everything we have come to expect. Strange stories of all the great and good of the American twentieth century, from the very very famous to the known-in-certain-circles. Vidal's life has been not just more eventful than most, but lived at a more rarefied level; he was brought up among the renowned and the ruling classes, and so the line for him between the personal and the political has always been a thin one.

There, he is talking - initially - about his series of novels, Washington, D.C., Burr, 1876, Lincoln, Hollywood and The Golden Age, 'factional' accounts of the USA, which he refers to collectively as 'Narratives of Empire' but which his publishers keep insisting on branding as 'Narratives of a Golden Age.' Throughout Point to Point Navigation, Vidal is at pains to mention his fictional output at every opportunity, making a vain (in both senses) attempt to mark his patch in literary history as a novelist, rather than wit, essayist and polymath. But he can hardly be dissatisfied by how he is already remembered.During the next quarter century I re-dreamed the Republic’s history, which I have always regarded as a family affair. But what was I to do with characters that were – are – not only famous but even preposterous? When my mother was asked why, after three famous marriages, she did not try for a fourth, she observed, “My first husband had three balls. My second, two. My third, one. Even I know enough not to press my luck.”

And there is a good reason for his interest in remembrance, and how he will be viewed in retrospect. Vidal is now 81 years old, and the spectre of death shadows most of the book. There will not, we suspect, be a third volume. He is writing in "the awful year 2005," after his first full year spent without his partner of 53 years, Howard Auster, and making the move for health reasons back to LA and away from his beloved La Rondinaia, the extraordinary home on the cliffs of Ravello on the Amalfi coast in Italy, where he and Auster had lived since 1963.

The memoir is less structured than Palimpsest, taking almost a diaristic form as he reflects both on the things that happen to him during 2005, the events in the world, and the people he knew whose deaths invoke a flurry of anecdotes. If the book had been more orderly, there is no doubt that Vidal would have left the strongest material to the end, instead of one-third in where it now appears. This is his report of the death of his partner Howard Auster in November 2003: the long struggle from illness to illness, the childlike reduction in his life, and most movingly, an extraordinary account of how Vidal looked into Auster's still-alert eyes after his heart stopped and held his gaze as he watched life ebb away from him. It is worth, as they say, the price of admission alone and if it doesn't move you to weeping then you should have your tear ducts checked by a qualified professional.

So strong is the feeling of mortality throughout the book (assisted by the black cover) that it almost feels like a posthumous publication. Vidal is still vital however, and the effortless quality of his prose reminds us that although he is "moving, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked exit," he is still fully with us.

And I do not want to suggest that the book is overwhelmingly gloomy or morbid. There is plenty of Vidal's wit in evidence, and his contempt for the current (and most past) American administration, and his country's cultural mores.

Despite the occasional stretches where he mistakes his intimate knowledge of some lesser-known folk with our interest in them, the overall feeling of gratitude and what Martin Amis called "a transfusion from above" when reading Point to Point Navigation, means I can offer it only the highest praise. It is a perfect valediction for Vidal.A current pejorative term is narcissistic. Generally, a narcissist is anyone better looking than you are, but lately the adjective is often applied to those “liberals” who prefer to improve the lives of others rather than exploit them. Apparently, a concern for others is self-love at its least attractive, while greed is now a sign of the highest altruism. But then to reverse, periodically, the meaning of words is a very small price to pay for our vast freedom not only to conform but to consume.