Jonathan Safran Foer: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

I'm a bit of a sucker for a book that looks nice as well as reads nice. But rarely is the

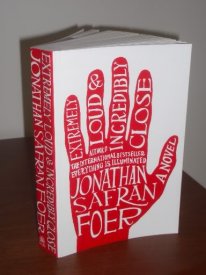

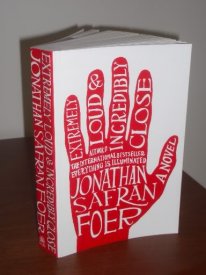

niceness of a book so intrinsic to the reading experience as with Jonathan Safran Foer's second novel which has just come out in the UK. Sadly Waterstone's weren't stocking the hardback, but even the hated trade paperback format is a thing of solid beauty.

I just love the bold design, the spine entirely filled with name and title, the smooth thick paper and, not least, the fact that my own left hand precisely fits the cover illustration when laid on top of it. And it doesn't end there: the inside is as well produced, with illustrations, colour pages, photographs and overtyping all enhancing the effect of the text.

Which is not to say that the book relies on all these things. In fact you could lose the fancy pages - 80 of them in total, which would reduce the page count from 320 to 240 - and the book would still be as good. Just not as

nice.

And it is a good book, very good indeed in my estimation. Mainly this springs from the voice of the primary narrator, Oskar Schell, a nine-year-old prodigy living in New York, who is forever inventing when he can't sleep (which is most of the time), learning new pieces of trivia, and otherwise occupying his life to make up for the great big hole in the middle of it. Oskar's father, Thomas Schell, was killed in the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001. He rang their home from his office six times, leaving messages each time, because Oskar - sent home from school along with all the other children - was too frightened to pick up the phone. He has never told his mother about the messages and the guilt and sense of impotence gives him, for a nine-year-old child, "very heavy boots."

Oskar's voice is playful and inventive (putting me in mind of Calvin from

Calvin and Hobbes), despite the solemn nature of the story and his inner feelings. In fact it is a great strength of the book that Oskar's feelings are expressed so minimally, coolly almost, so that when he tells us "I made a bruise," or bemoans that today he has "very heavy boots indeed," we apply our own horror and sympathy to him, and he remains charming and funny under all the subtly expressed pain. It's hard to do his tone justice in a short extract, but this is the sort of thing you get:

Isn't it so weird how the number of dead people is increasing even though the earth stays the same size, so that one day there isn't going to be room to bury anyone anymore? For my ninth birthday last year, Grandma gave me a subscription to National Geographic, which she calls "the National Geographic." She also gave me a white blazer, because I only wear white clothes, and it's too big to wear so it will last me a long time. She also gave me Grandpa's camera, which I loved for two reasons. I asked why he didn't take it with him when he left her. She said, "Maybe he wanted you to have it." I said, "But I was negative-thirty years old." She said, "Still." Anyway, the fascinating thing was that I read in National Geographic that there are more people alive now than have died in all of human history. In other words, if everyone wanted to play Hamlet at once, they couldn't, because there aren't enough skulls!

Breaking up Oskar's narrative are monologues by his paternal grandmother and (estranged) grandfather, so that in the end we get the dead man, Thomas, addressed by both his parents and his child. These are equally accomplished, if less skittish than Oskar's, and so give a more mature and reflective account of loss, and provide most (but not all) of the emotional peaks of the book. And breaking up everything are those photos, and illustrations, and red-pen markings; not to mention a highly risky conceit at the end of the book, where were are given our own representation of a flicker book Oskar wants to make, showing someone leaping to their death from one of the twin towers: in reverse, so that it looks as though he is floating up to safety. Whether this works for you, or is a step too far, probably depends on whether the book has won you over up to that point. For me, it did. Otherwise, most of the illustrations are superfluous, nice but not needed, though occasionally they work to great effect. Here, for example, is what happens when Oskar's grandfather, who cannot speak and has to write everything down, finds himself running out of space before he can finish his last letter to his dead son:

View attachment aphotos13.flickr.com_16126438_5a3e33b990.jpg

View attachment aphotos9.flickr.com_16126439_6b2ac644ec.jpg

But even so, it's the writing that makes

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close work so well. Safran Foer has an extraordinary ability for his 28 years (damn him), expertise in teasing out the right verbal trope at the right moment, knowing when to leave a joke unexplained and adept at creating effortless dialogue, even for an unrealistic-realistic nine-year-old like Oskar. I found

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close to be that rare thing, an utterly satisfying and complete experience, and a leap on from his debut novel

Everything is Illuminated, which was too quick at times to blaze with cleverness and lacked the accessible clarity which shines through this book. It's a masterpiece.